Steven White is an Associate Lecturer in English Literature at Anglia Ruskin. He submitted his thesis on “Representations of Society in Conservative Poetry, 1790-1798” in August 2016. His research interests lie broadly in the fields of political writing of the long nineteenth century, the relationship between literature and the formation of ideologies, and music journalism in the Victorian period. Twitter | Email

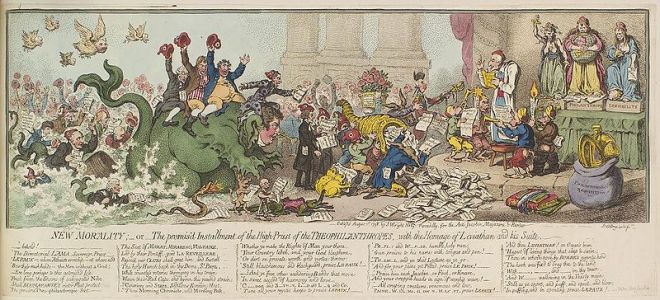

New morality; -or- the promis’d installment of the high-priest of the theophilanthropes, with the homage of Leviathan and his suite.

James Gillray, 1798

Hand-coloured etching

© British Museum

Since reading Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France for the first time in 2008 I have been fascinated by the conservative opposition to the ideals of the French Revolution. Burke was for a long time reductively held up as, to borrow Kevin Gilmartin’s phrase, “a simple index of conservatism” – a political force which “we now correctly understand to have been more complex and internally differentiated” than previously understood (8). Still, there is much work which remains to be done in the field. My research centres on a genre of writing which has previously been left more or less untouched by scholars, and, in fact, cannot be said to have been fully recognised as a genre of writing in its own right at all – that of conservative or counter-revolutionary poetry.

It is strange that so little should have been said about conservative poetry. My research has found that no fewer than six hundred poems were published between 1790 and 1798 which in some identifiable sense worked to preserve the established order in Britain and/or to resist the changes threatened by the French Revolution. This number is based only on the poems that were published through mass media channels – that is newspapers, magazines, periodicals, broadsides, songsters and the like. It does not include those published as or exclusively as volumes of poetry (this would take the number up still further). By any measure, it is a significant body of writing in terms of size alone. But its real significance lies in the potential of such poetry as an ideological weapon, as poetry was possessed of a potential for crossing divisions of class, education and sex in a way that perhaps no other medium was.

Continue reading →