by Edwin John Moorhouse Marr

My first introduction to George Eliot was not an altogether agreeable one. I had to read Adam Bede as part of my undergraduate degree, and I found it symptomatic of all the weaknesses of the Victorian novel. It was long and dull and lavished unnecessary descriptions, it wallowed in sentimentality, and I thought that the characters were overly moralistic and pious. It certainly succeeded in putting me off reading another Eliot novel for a considerable time. Then once again Eliot cropped up on the reading lists, this time for my MA in the form of Middlemarch. I stared at the book in its enormity, and dreaded 800 pages of further sentimentalising, piety and endless descriptions of gateposts. It took up until Dorothea’s heart wrenching arrival into Rome to realise I had been catastrophically wrong. Middlemarch, with its sympathetic representations of humanity and its appeal, not for grand empty posturing, but for real, achievable acts of benevolence, spoke to me directly, and represented a philosophy to aspire towards. Thus started a strange sort of love affair with George Eliot, and I quickly read Daniel Deronda, followed by the bizarre and supernatural The Lifted Veil. Next came her tale of forgiveness and second chances, Silas Marner. I then turned to the story I found most heart breaking of all, The Mill on the Floss, where I can still hear Maggie calling out her brother on his hypocrisies and crying out to a world that never finds her good enough. I then read Scenes of Clerical Life; with its bold themes of alcoholism and domestic violence, I realised why this collection of three stories launched Eliot onto the literary scene. I am still to read her Renaissance novel Romola, which has sadly been put onto something of the backburner by PhD reading lists.

Having fallen so quickly and rapidly in love with George Eliot, the next step for me was to go on the Eliot trail. I have always been fond of literary pilgrimages of authors I’ve admired, whether to the Brontë Parsonage in Haworth, Dickens’ house in London, or Sylvia Plath’s grave in Heptonstall. But going on the Eliot trail is a rather more difficult affair. For a start, there is no dedicated museum to Eliot, nor is there a preserved house in the way there is for Gaskell, Dickens or the Carlyles. In the summer of last year, I made a start by visiting Eliot’s grave at Highgate Cemetery. A stone needle, Eliot’s grave stands tall amongst the other headstones, with ‘Mary Ann Cross’ written underneath her literary pseudonym, a reminder of both the woman behind the novelist and her short and rather unexpected marriage to the banker John Cross. The true love of Eliot’s life and husband in all but deed, George Henry Lewes is also buried at Highgate, but he is not deemed important enough to be listed on the map given out at the entrance with the £4 admittance fee. After asking, it turns out that Lewes is buried behind Eliot in a small grave covered over with ivy and looking rather the worse for wear. He is lurking in the shadows, just as he was in life, offering Eliot his support behind the scenes, whether through encouraging her to publish books she didn’t feel were good enough or hiding unsavoury reviews. Eliot and Lewes were ever two sides of an ideal partnership, and even though Eliot may have taken the name ‘Cross’ at the time of her death, it is still Lewes who is standing behind her in death.

Having seen where Eliot died, the next step was to see where she lived, and this involved a trip to Nuneaton in Warwickshire. Mary Ann Evans was born in 1819 on South Farm on the Arbury Hall estate where her father worked as the estate manager. Arbury Hall is still owned by the same Newdigate family who were there in Eliot’s day, but alas they do not grant access to the estate beyond a few bank holidays in the summer, so it was not possible on this occasion to see the house Eliot was born in. With Mary Ann aged just one year old, the Evans family moved to Griff House on the outskirts of the Arbury estate and on the edge of Nuneaton, and this house is rather more accessible. After arriving on the 12:06 Crosscountry service from Cambridge, Griff House was my first port of call, a short taxi ride from the train station.

Having seen where Eliot died, the next step was to see where she lived, and this involved a trip to Nuneaton in Warwickshire. Mary Ann Evans was born in 1819 on South Farm on the Arbury Hall estate where her father worked as the estate manager. Arbury Hall is still owned by the same Newdigate family who were there in Eliot’s day, but alas they do not grant access to the estate beyond a few bank holidays in the summer, so it was not possible on this occasion to see the house Eliot was born in. With Mary Ann aged just one year old, the Evans family moved to Griff House on the outskirts of the Arbury estate and on the edge of Nuneaton, and this house is rather more accessible. After arriving on the 12:06 Crosscountry service from Cambridge, Griff House was my first port of call, a short taxi ride from the train station.

I was aware before arriving that Griff House has been turned into a Beefeater, but I was pleasantly surprised how much of Eliot is still present. There is a sign giving some information about Eliot’s life, as well as some pictures of how the house looked before it became a pub. Now, there is a modern extension on the side, but it is not difficult to imagine how the house would have looked before this rather cumbersome intrusion of modernity was added. Inside, the old fireplaces remain, as do the flagstone floors and the old windows, and the front door does not appear to have changed either. Mary Ann Evans lived in Griff House until she was twenty, and despite the couple curled up in the corner over their pints of beer, it is still possible to imagine her walking through these old rooms that remain open to the public.

I was aware before arriving that Griff House has been turned into a Beefeater, but I was pleasantly surprised how much of Eliot is still present. There is a sign giving some information about Eliot’s life, as well as some pictures of how the house looked before it became a pub. Now, there is a modern extension on the side, but it is not difficult to imagine how the house would have looked before this rather cumbersome intrusion of modernity was added. Inside, the old fireplaces remain, as do the flagstone floors and the old windows, and the front door does not appear to have changed either. Mary Ann Evans lived in Griff House until she was twenty, and despite the couple curled up in the corner over their pints of beer, it is still possible to imagine her walking through these old rooms that remain open to the public.

After exploring the inside of Griff House, I then headed outside to discover the outhouses left over from when the house was a farm. The Eliot Society is currently renovating some of them, and you can see bricks and mortar lying around. Certainly, it is not before time, as they are in a terrible state of repair, with cracks in the brickwork with some of the buildings feeling that the pressure of a finger could demolish them. Still, away from the noise of the pub it is very quiet, and it is easy to imagine the Evans family moving around these buildings, completing their farming duties for the day, although the gas bottles and vats of rapeseed oil feel rather incongruous against the historic structures.

After Griff House, I then went to the Nuneaton Museum and Art Gallery in the centre of town, another short taxi ride away. The museum has two wings, one looking at local history and the other dedicated to George Eliot. After trying on an Eliot mask and briefly enjoying embodying my literary hero, I then appreciated the international items, a street sign from Israel with ‘George Eliot Street’ written in Hebrew, and one of Eliot’s novels translated into Japanese, showing how she continues to be a globally celebrated author.

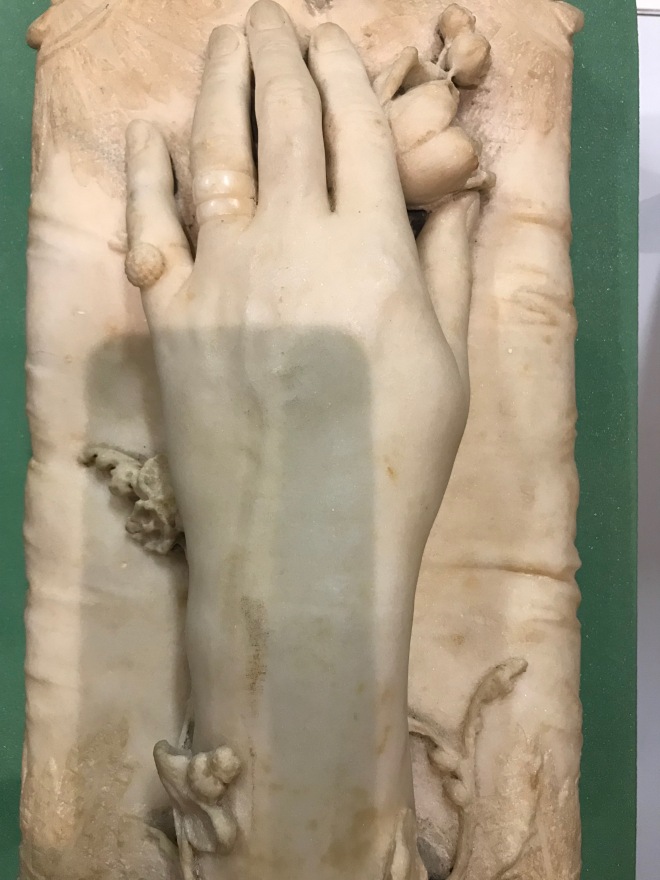

In the next room, there were some of Eliot’s personal possessions: a toiletry set, a bell, a mourning hood, and her mirror. As I stared into the mirror, and saw my own face reflected back, I thought of all the times Eliot would have done the same. It is well-known that Eliot was preoccupied by her appearance, even once denying that a picture had been taken of her. In fact, a photograph had been taken in 1858, but as Kathryn Hughes has written, ‘Marian did not like it, with good reason: the conventionally coy pose made her features look even heavier than usual’. Did Eliot stare into this looking glass, scrutinising the lines of her face and wishing to have had a smaller nose or a less severe chin? In the next case was an even more intriguing object, a stone model of Eliot’s hand. Unlike the Brontës with their impossibly small gloves and shoes, Eliot’s hand feels real somehow, a normal size that you could reach out and shake without danger of crushing. It certainly is a strange connection to the deceased to see their hand in front of you, so perfectly formed, even down to the jewellery and veins.

In the final section of the museum, they have a reconstruction of Eliot’s sitting room, complete with some rather dodgy waxworks of Eliot, Lewes and Cross. Still, the diorama has some of Eliot’s original items including a screen and footstool.

In the final section of the museum, they have a reconstruction of Eliot’s sitting room, complete with some rather dodgy waxworks of Eliot, Lewes and Cross. Still, the diorama has some of Eliot’s original items including a screen and footstool.

Having left the museum, I then saw the memorial stone to Eliot by the river in the middle of Nuneaton, before seeking out the statue to Eliot located on the high street. Staring downward thoughtfully and perhaps a tad demurely, there is nonetheless a sense of movement about the piece, unusual for a metal statue, as if Eliot is about to get down from the plinth and invite you to one of the Sunday morning receptions she hosted with Lewes in London. I finished the day with a drink in the George Eliot pub, in Eliot’s day a coaching inn during the final days of the stagecoach world, and now a bold symbol of this town’s pride in its famous literary hero. After Nuneaton, Eliot moved to Bird Grove, Coventry in 1841 (now an Islamic school). It was during this period of her life that Eliot met the intellectuals Charles and Cara Bray, triggering Eliot’s move away from religion, and her distancing from her father. In 1850, Eliot moved to London where her literary career really took off as she became editor of the Westminster review. The rest as the say, is history, although even in London, a city with a proud habit of preserving and celebrating its history, there is no Eliot house open to the public. With her Thames-side home recently selling for £17 million, it would have to be a charity with deep pockets.

Having left the museum, I then saw the memorial stone to Eliot by the river in the middle of Nuneaton, before seeking out the statue to Eliot located on the high street. Staring downward thoughtfully and perhaps a tad demurely, there is nonetheless a sense of movement about the piece, unusual for a metal statue, as if Eliot is about to get down from the plinth and invite you to one of the Sunday morning receptions she hosted with Lewes in London. I finished the day with a drink in the George Eliot pub, in Eliot’s day a coaching inn during the final days of the stagecoach world, and now a bold symbol of this town’s pride in its famous literary hero. After Nuneaton, Eliot moved to Bird Grove, Coventry in 1841 (now an Islamic school). It was during this period of her life that Eliot met the intellectuals Charles and Cara Bray, triggering Eliot’s move away from religion, and her distancing from her father. In 1850, Eliot moved to London where her literary career really took off as she became editor of the Westminster review. The rest as the say, is history, although even in London, a city with a proud habit of preserving and celebrating its history, there is no Eliot house open to the public. With her Thames-side home recently selling for £17 million, it would have to be a charity with deep pockets.

I did not know what to expect from this trip to Nuneaton. I was worried that there would be little of Eliot left. That Griff House would just feel like any other Beefeater, and the museum would have nothing more than a cabinet dedicated to Eliot alongside other local celebrities. But I was pleasantly surprised, and found a town that celebrates its literary hero. It is just a shame that there isn’t a house preserved for Eliot in the way there are for her contemporaries. One can’t help but feel that if Beefeater invested in restoring the original part of Griff House into a museum to Eliot, the income they would draw from hungry and thirsty literary tourists, visitors and conferences and events held there, would more than cover their outlay.

I did not know what to expect from this trip to Nuneaton. I was worried that there would be little of Eliot left. That Griff House would just feel like any other Beefeater, and the museum would have nothing more than a cabinet dedicated to Eliot alongside other local celebrities. But I was pleasantly surprised, and found a town that celebrates its literary hero. It is just a shame that there isn’t a house preserved for Eliot in the way there are for her contemporaries. One can’t help but feel that if Beefeater invested in restoring the original part of Griff House into a museum to Eliot, the income they would draw from hungry and thirsty literary tourists, visitors and conferences and events held there, would more than cover their outlay.

What an inspiring description of the Eliot trail. And perfect illustrations to complement it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing the narrative of your biographical discovery of George Eliot’s life. This reads like somewhere between literary biography and travel writing, and I am inspired to follow her trail in your footsteps. I particularly enjoyed the images!

LikeLiked by 1 person