Steven White is an Associate Lecturer in English Literature at Anglia Ruskin. He submitted his thesis on “Representations of Society in Conservative Poetry, 1790-1798” in August 2016. His research interests lie broadly in the fields of political writing of the long nineteenth century, the relationship between literature and the formation of ideologies, and music journalism in the Victorian period. Twitter | Email

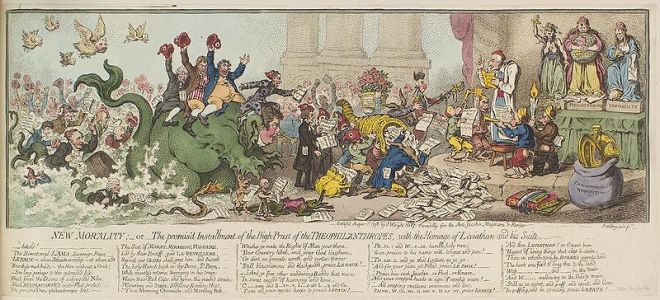

New morality; -or- the promis’d installment of the high-priest of the theophilanthropes, with the homage of Leviathan and his suite.

James Gillray, 1798

Hand-coloured etching

© British Museum

Since reading Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France for the first time in 2008 I have been fascinated by the conservative opposition to the ideals of the French Revolution. Burke was for a long time reductively held up as, to borrow Kevin Gilmartin’s phrase, “a simple index of conservatism” – a political force which “we now correctly understand to have been more complex and internally differentiated” than previously understood (8). Still, there is much work which remains to be done in the field. My research centres on a genre of writing which has previously been left more or less untouched by scholars, and, in fact, cannot be said to have been fully recognised as a genre of writing in its own right at all – that of conservative or counter-revolutionary poetry.

It is strange that so little should have been said about conservative poetry. My research has found that no fewer than six hundred poems were published between 1790 and 1798 which in some identifiable sense worked to preserve the established order in Britain and/or to resist the changes threatened by the French Revolution. This number is based only on the poems that were published through mass media channels – that is newspapers, magazines, periodicals, broadsides, songsters and the like. It does not include those published as or exclusively as volumes of poetry (this would take the number up still further). By any measure, it is a significant body of writing in terms of size alone. But its real significance lies in the potential of such poetry as an ideological weapon, as poetry was possessed of a potential for crossing divisions of class, education and sex in a way that perhaps no other medium was.

As John Gardner has argued, poetry was a “democratic” medium: it was “cheap” to produce (and indeed to buy), it benefitted from “subtlety, compression”, it could be committed to or imposed upon one’s “memory” and enjoyed a form of “democratic transmission” in “that even the illiterate can have poetry” because of its orality (3). It was a form, too, through which an individual might consume a text and receive its ideas almost by accident. A poem might be encountered by idly thumbing through a friend’s magazine, or by reading a broadside ballad without realising there was a political dimension to it, or by hearing the latest loyalist song sung in a public house, or by watching a play to which a topical prologue or epilogue had been added. Poetry had the potential to influence not just the intellectual elite, or the middle class consumers in the literary market place, or the average working man – but all of them. Some poems targeted one particular group, others were broad and available to an almost universal readership. They were, therefore, vehicles capable of conveying a form of popular conservatism to the average man or woman.

I use here the phrase “popular conservatism” as distinct from what might be thought of as an intellectual, or theoretical, or abstract notion of conservatism. My research does not explore what it meant to identify as a conservative in an age of revolution. It is interested in the way individual authors sought to make ordinary people actively believe in the rectitude of the established order, and to make them want to take action to ensure that it would be preserved in the face of potential revolutionary tumult. The conservatism found in the poetry of the 1790s was not a philosophical construct, or even in any meaningful way an intellectual concept. It was a practical means of mobilising support behind the established order. What my research does above all else is examine the means by which poets sought to achieve this aim. To explore the various techniques, arguments, images, and so on used to try and make the reader perceive the world and their role in it in such a way as to make them determined to maintain the status quo.

The driving questions which have motivated my research, and which poetry is better equipped to answer than any other written medium from the era, centre on how conservatives justified the most unsavoury or indefensible aspects of existing society. Particularly, how did they justify oppression and suffering to those who were oppressed and who suffered at the hands of the status quo? How did they sell poverty to the poor? What did labouring poets say in defence of their hardship? How did they legislate for the existence of starvation? How did they justify to women their exclusion from full participation in society? What did women themselves say to promote their existing circumscribed lot? The transcendent appeal of poetry, and its ability to cross social boundaries, means that answers to these questions can be found in the individual texts that comprise the genre. In the poetry pages of publications like The Gentleman’s Magazine, The European Magazine, The Anti-Jacobin, The True Briton and The Weekly Entertainer. And in the songs and ballads produced by organisations like John Reeves’s Society for the Preservation of Liberty and Property from Republicans and Levellers, and Hannah More’s Cheap Repository.

I have written a number of short articles for The Literary Encyclopaedia relating to my research. One on the conservative periodical, The Anti-Jacobin, and two on individual poems from that publication: “New Morality” and “The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-grinder”.

Works Cited

Gardner, John. Poetry and Popular Protest: Peterloo, Cato Street and the Queen Caroline Controversy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Gilmartin, Kevin. Writing Against Revolution: Literary Conservatism in Britain, 1790-1832. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Work in Progress is a regular feature on our blog where members contribute short articles about their current research. If you’d like to contribute a piece, please get in touch!